All That Glitters…

It seems singularly appropriate that The Golden Ticket started with my desire for an actual golden ticket, though not to a chocolate factory. No, I wanted a ticket to Italy.

Let me explain. When I was 26, my husband and I had our first child—a winsome, blond, dimpled, chortling baby who rolled over, sat up, crawled, and walked exactly on schedule. He also avoided eye contact, arched away when we held him, and repeated phrases he heard on television, though he did not call us “mama” or “daddy” or spontaneously put words together. When he was two and a half, he was diagnosed with autism.

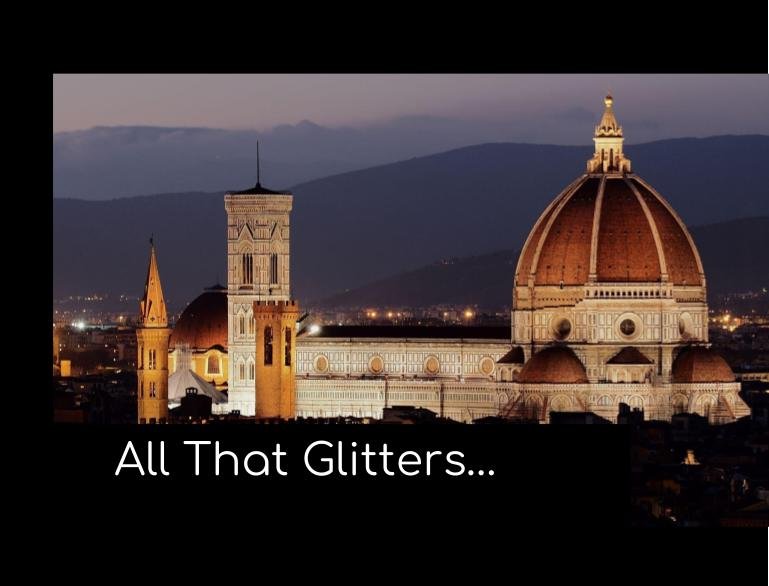

Well-meaning friends sent us copies of Emily Kingsley’s essay, “Welcome to Holland,” an essay in which Kingsley likens having a child with Down’s Syndrome to thinking you’re going on vacation to Italy and instead discovering that your plane has landed in Holland. After mourning everything you won’t get to experience (gondolas in Venice! The Sistine Chapel! The PIazza della Signoria!), you come to realize that Holland, with its tulips and windmills and Rembrandts, is beautiful too. But my husband and I were 28 years old, educated and ambitious (I had just finished my PhD in comparative literature at UCLA, he was completing his psychiatry residency at Stanford), and we were not ready to adjust our expectations. We did not want to go to Holland. We wanted to twirl homemade pasta around our forks in a candlelit restaurant and contemplate the quilt of umber and red rooftops beneath the Duomo.

My husband and I are book people, so we went to the Lane Medical Library at Stanford and checked out every book on autism we could find. This was 1997, and what we found were mostly medical texts that laid out, in unsparing detail, the dismal future that lay ahead for all of us. We also checked out some books about Applied Behavioral Analysis—a system of rewards and reinforcements that break down complex tasks (asking a question, putting on shoes, washing hands) into small, easily managed components and rewarding the child for completing each component, eventually chaining the parts into a larger whole. There was a third genre of book that the psychiatrist who diagnosed our son advised us not to read; she called them “parent testimonials.” Parent testimonials were written by parents of autistic children who had refused to give up on their children until either Applied Behavioral Analysis or the power of prayer (or sometimes both) precipitated a complete recovery. Complete recovery meant that their child had become indistinguishable from other typically developing children. Complete recovery, said the diagnosing psychiatrist, was a misleading term. It might give us false hope or lead us to form unrealistic expectations.

Did we check out those books? We did. Of course we did. We also rushed out to a school supply store, bought a classroom table and two diminutive yellow plastic chairs, and started an intensive ABA program.

Our son became an ABA rock star practically overnight and rocketed up the developmental charts. But the more skills he gained, the more my husband and I wanted. We would have Italy, or its neurological equivalent: our son would talk, he would ride a bicycle, he would have playdates, he would be on a sports team, he would learn to drive, he would go to college.

In Roald Dahl’s Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, wanting a golden ticket is only the first step down a slippery slope. Once inside the factory, there is so much more to want. Violet Beauregarde wants to chew the chewing-gum meal. Augustus Gloop wants to drink from the chocolate river. Veruca Salt wants a squirrel. Mike Teavee wants… well, his name says it all. My husband and I wanted a story with a happy ending. It would go like this: a bit of trouble at the outset, hard work to set everything straight, and—voilà!—a child who was indistinguishable from any other typically developing child.

I also wanted something else: to write about what it’s really like to raise a child with autism, how surreal and difficult and dark and also absurdly funny it could be. The parent testimonials we had read were earnest and artless saccharine; my husband and I were sarcastic and snarky and maybe more cocky than we should have been. Three months after our son was diagnosed, a friend sent me David Sedaris’ Naked, and as soon as I read it, I thought, I’m going to write a book like that. Smart and funny and acerbic and self-aware except instead of being about a neurotic gay Greek guy with a crazy family, it’s going to be about a neurotic Russian-Jewish woman with an autistic kid who helped the autistic kid not be autistic anymore.

Here’s the thing: you can’t really write that book until you’ve had two more children, worked in undergraduate admissions at Stanford, and opened your own college counseling practice. You also can’t write it until your oldest son—who becomes a varsity wrestler, who drives a car, who goes away to college—becomes suicidally depressed in his early 20s because in teaching him how to be indistinguishable, you’ve also made him aware of everything he doesn’t know, all the ways he can’t measure up. You can’t write it until his younger brother and sister also begin to struggle. And all the while, you work with some of the most ambitious and highly accomplished students in the world, students who dream of going to colleges that are so hard to get into that it puts you in mind of Luke 18:25. That passage about a camel going through the eye of a needle.

The ancient Greeks called this peripeteia—a fearsome humbling, a catastrophic fall made all the more devastating because the protagonist’s hubris is what brings about the reversal in the first place. The psychiatrist who diagnosed our son was right: the testimonials did lead us to form unrealistic expectations, and we acted on those expectations, and now our world was in pieces. But what of my students’ expectations of being accepted to colleges that rejected 96 percent of their applicant pool? What of their parents, many of whom, like my own parents, had come to the US in pursuit of their own golden tickets—political and economic stability, freedom of expression, the bragging rights that come with acceptance to a college that validates years of striving and struggle?

Some of the students and parents I work with measure success strictly by whether they get into what I call highly rejective schools. (There’s even an acronym for them: HYPS, which stands for Harvard, Yale, Princeton, Stanford. Sometimes the other Ivies or MIT are thrown in as a grudging afterthought.) And while I don’t agree with their thinking, I recognize their aspirations on a cellular level; they’re the same aspirations I entertained when I was 28 and wanted a ticket to Italy more than anything else in the world.

Here’s the funny part: my husband and I actually had a trip to Italy planned for fall of 1997. When our son was diagnosed in May of that year, I told my mom we were canceling the trip. She said, “Absolutely not.” She and my father took on my son’s rigorous ABA schedule, plus occupational therapy, plus speech therapy appointments, and my husband and I flew to Italy, where we gaped at ceiling of the Sistine Chapel and climbed the Duomo and fed the pigeons on the Piazza San Marco and ate homemade pappardelle in candlelit restaurants. And then we returned home, and our son—who we were convinced would be as indifferent to our return as he was to our departure—lunged out of my mother’s arms shouting, “Mommy! Daddy!” and I had never seen anything more beautiful in my life.

For more of my reflections about college admissions, parents, children, and books ranging from Charlie and the Chocolate Factory to The Odyssey, check out my memoir The Golden Ticket: A Life in College Admissions Essays.